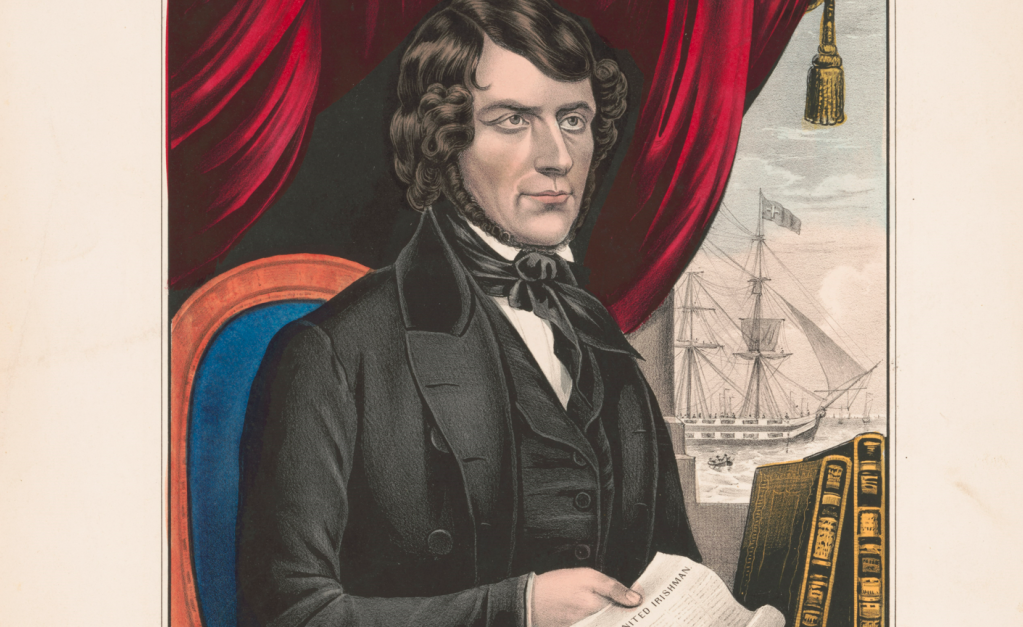

John Mitchel has the most complex legacy of all the Young Irelanders. Mitchel was one of the most powerful polemicists of the 19th century who did more than most to foment the Young Ireland rebellion. As Sinn Fein founder Arthur Griffith wrote, one reason that the 1848 rebellion was a failure was “because there was no second Mitchel in Ireland when the first Mitchel was hurried off on a British gunboat”. Mitchel’s writings on British imperialism and the supposed genocide of the Famine had profound impact on Griffith and other Irish revolutionaries of the early 20th century. Even non-revolutionary William Butler Yeats admired the violence and passion of his work, especially his great Jail Journal, saying Mitchel was the only Young Irelander with “music and personality”.

However ,Yeats also thought him “devil-possessed” and Mitchel’s hatred of England, an “almost psychotic Anglophobia,” as Roy Foster put it, has become distasteful in modern independent Ireland. Even more troubling is Mitchel’s vehement support for American slavery which have led to calls in 2020 to pull down a statue of him in his Newry hometown and rename John Mitchel Place to Black Lives Matters Place. While Newry City Council refused the requests saying 19th century figures could not be held to 21st century views, Mitchel was extreme even in his own day. In America Mitchel admitted to William Smith O’Brien that many people “don’t wonder that the British Government found it necessary to get rid of me.” Smith O’Brien knew the truth of the charge but acknowledged Mitchel’s complexity when he wrote to his wife saying, “while you nor I agree with the political views of Mr Mitchel, there are few persons more beloved by his private friends and family than this formidable monster”.

Whatever of the monster, Mitchel got many of his formidable qualities from his parents. His mother Mary Haslett was the daughter of a 1789 United Irishman from a prominent Derry family and known as an “intelligent and forceful woman”. Her husband John Mitchel was a Unitarian minister who split from the Orange wing of the Presbyterians and supported Catholics in their quest for civil and political rights. Their son John was born in Derry in 1815 but they moved to Newry where Rev Mitchel got behind the Catholic candidate in the 1829 election, earning him the nickname “Papist Mitchel.” John inherited his father’s religious tolerance and his belief in the sanctity of personal conscience. He also learned how to stand unwaveringly on principle even while fighting a losing battle, something that remained throughout his life. An asthmatic, Mitchel junior had the “toughness and fixity of purpose that often characterises those who habitually struggle for breath”, as Thomas Keneally put it.

At school in Newry and later at Trinity College Dublin, Mitchel’s closest friend was fellow Protestant John Martin, a farmer’s son. Martin was another asthmatic and he was one of the few people whose advice Mitchel valued. They would share a lifetime of adventures together in Young Ireland and later exile. After Mitchel graduated from Trinity, he studied under a solicitor in Newry where he was entranced by a 16-year-old neighbouring beauty named Jane (Jenny) Verner. When her father arranged to take Jenny away to France, she and Mitchel eloped to Chester where they sought a marriage licence. They were discovered by her parents and police. Mitchel was arrested and spent 16 days in Kilmainham prison, the first of many times behind bars. A judge dismissed abduction charges and though the Verners took Jenny away to a secret location, Mitchel tracked her down and successfully wooed her again, marrying in February 1837 with John Martin his best man. Over the next 38 years the remarkable Jenny bore Mitchel six children and followed him uncomplainingly across three continents and nine cities, caring for his family while he fought for his beloved causes.

As a young barrister in Banbridge Co Down, Mitchel represented poor Catholics who were victims of the discriminatory Ulster legal system and had a reputation as a Protestant advocate Catholics could trust. Mitchel and Martin became supporters of Repeal after O’Connell visited Newry in 1839 and they joined the Repeal Association in 1843. Mitchel first met Gavan Duffy, then editor of the Belfast Vindicator, in 1841. Oddly, Duffy described him in a similar way to his first impression of Meagher, “rather above the middle size and well made”. When the Nation started up, Mitchel offered his contributions. He was particularly enchanted with the ideas of fellow Protestant Thomas Davis and visited him on trips to Dublin. The pair collaborated on an editorial called the “Anti Irish Catholics”, a title which raised O’Connell’s ire, even though it said Irish Catholics had flourished once before and could do so again. Duffy also got Mitchel to write a biography of 16-17th century Irish hero Hugh O’Neill for the Nation‘s Library of Ireland which was serialised in the paper.

After Davis’s death in September 1845 Duffy hired Mitchel to become editor of the Nation and he moved to Dublin with his family. He soon ran into trouble in an article about how Repealers should deal with the spread of railways in Ireland. If railways were used to move troops, said Mitchel, Repealers could sabotafe them, breaking down an embankment or lifting rails while rails and sleepers could be turned into pikes and barricades. Mitchel claimed he was only suggesting what “a railway may and may not do,” but instructions on violent revolution were anathema to O’Connell who protested this call for his wardens to destroy property. What O’Connell didn’t say was that it was partially his property – he was one of the first shareholders in the Dublin and Cashel railway. Dublin Castle was also alarmed at the article and charged publisher Duffy with sedition, though his counsel successfully argued in court it was merely a hypothetical argument.

Mitchel likely first met Thomas Francis Meagher at a Dublin meeting of the ’82 Club, a social club named for the Volunteers who successfully demanded a semi independent but Protestant Irish parliament in 1782. Club members wore a military-style tailored green and gold uniform and talked of independence in a cosy club setting without the rancour of Repeal meetings. Here Mitchel heard Meagher make a speech about Davis. As he warmed to his subject, Meagher’s Stonyhurst College accent subsided “under the genuine roll of the melodious Munster tongue”.

The married northern Irish Protestant minister’s son and the single southern Irish Catholic merchant’s son were an odd match, Mitchel as intense as Meagher was playful. Yet they became firm friends that day. The following morning Meagher and Mitchel met again at the Nation’s new editorial office on D’Olier St. They walked towards Donnybrook in non-stop conversation. “What eloquence of talk was his!” Mitchel enthused. Meagher did not speak about politics but about his women problems and his college days. They walked back to Mitchel’s house where Meagher met Jenny and stayed for dinner. “Before he left he was a favourite with all our household and so remained until the last,” Mitchel wrote. As the year ended, they would be on the same political wavelength, united in opposition to another likely political alliance between O’Connell and the Whigs. Meagher became the mouthpiece for Young Ireland in Conciliation Hall just as Mitchel became its wordsmith in the Nation. While never as close as Mitchel and Martin’s, it was a friendship that would inspire a national flag as well as survive rebellion, transportation, escape to America and even a war that put them on opposite sides. But as 1845 ended a new challenge emerged with disturbing news of the failure of Ireland’s main food crop – the potato.