I decided this week to cast my Brisbane city council vote in advance of polling day and that meant a long walk to the pre-poll office in Kedron Heights. It was an excuse to go somewhere new in my neighbourhood. I’d often passed Lutwyche Cemetery while driving up Gympie Rd but had never visited it. Though the graveyard has had no interments in three decades and is mostly ignored apart from the occasional dog walker, it remains a beautiful place, rich in history.

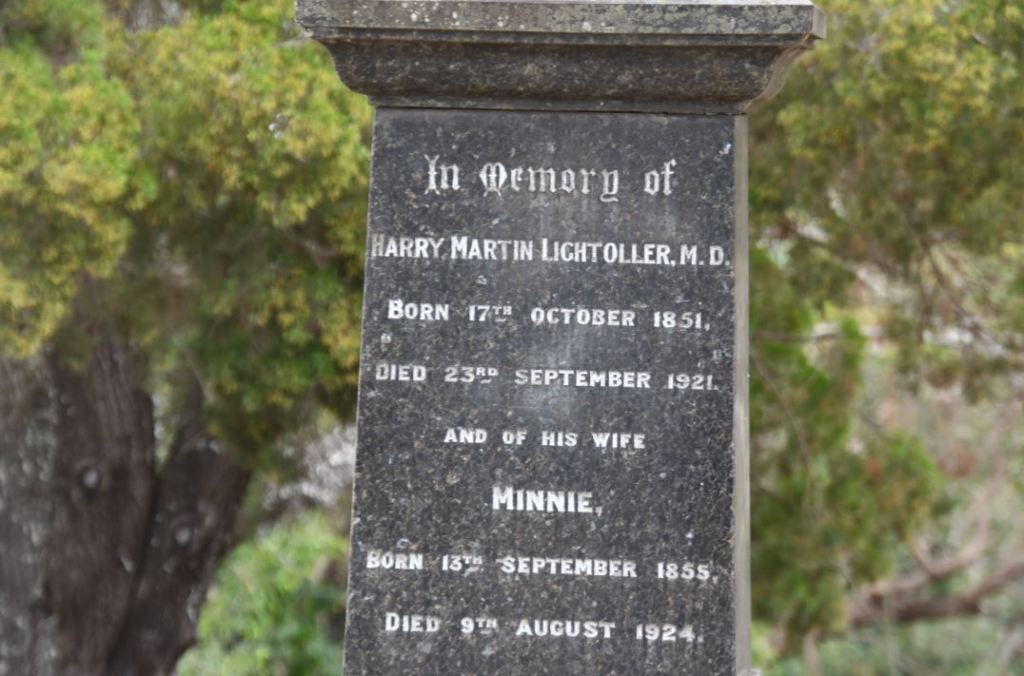

The cemetery and nearby suburb are named for 19th century politician and judge Alfred Lutwyche. Lutwyche was a NSW attorney-general who became Queensland’s first resident judge after it became a colony in 1859. He became the colony’s first supreme court judge two years later. Lutwyche lived in a grand house on Nelson St in my own next door suburb of Wooloowin and died in 1880. He was buried in St Andrew’s Anglican churchyard, though the cemetery named for him had just opened. Brisbane Cemetery (now Toowong Cemetery) had opened a few years earlier, but was already overcrowded and the growing city needed a second cemetery. In 1877 the Courier reported a council debate where “citizens of the village of Lutwyche” were lobbying for a public hall and reading room, and there was also “a sum on the estimates for a cemetery at Lutwyche”. Building began in the new year and by April the Church of England portion was consecrated. Five-year-old Walter Silcock was the first burial on August 4 that year.

During the Second World War, authorities built a War Graves section to bury 389 soldiers, both identified and unidentified. The remains of nine servicemen from the First World War were also moved to this section. The Imperial War Graves Commission erected the Cross of Sacrifice in 1950 using Helidon freestone.

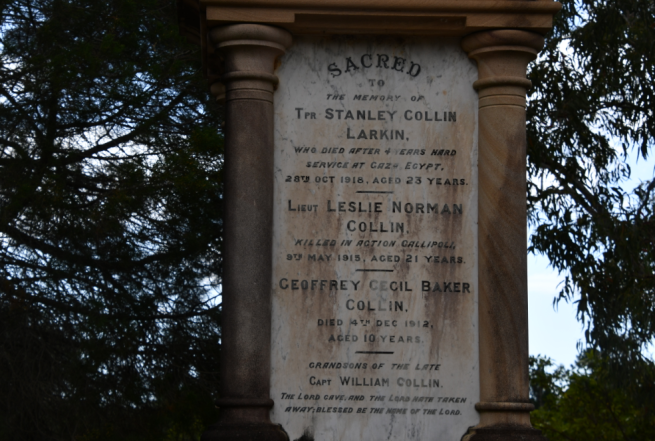

The most famous of the First World War graves is William Edward Sing’s. Billy Sing was a sniper at Gallipoli who killed up to 300 Turkish soldiers. Born in Clermont to an English mother, he suffered racial prejudice on account of his Chinese father. He kept his head down, becoming a stockman and became an expert shooter. Recruiters agonised over his “unsuitable background” before accepting him into the army in 1914, aged 30. The rugged Gallipoli terrain was made for snipers such as Sing whose spotter was the later best-selling author Ion Idriess, and he quickly became deadly. The Turks assigned their best marksman against him in vain. Fellow soldiers witnessing Sing’s marksmanship dubbed him “The Assassin”. Later in the war he moved to the western front where he was not as effective, and was wounded in the trenches before gas exposure ended his military career. Suffering from injuries, he failed at farming and mining and remained in poverty after the war. He died in obscurity in Brisbane in 1943. This large memorial was unveiled for him at Lutwyche in 2016.

James Brennan was a little known Queensland politician who served in turbulent times. Brennan was born in Scotland and emigrated to Australia in his 20s, taking up mining at Gympie. He later worked for a meat export company in Brisbane and Townsville, and from 1902 managed a Rockhampton meatworks. In 1907 he stood for election as a Kidstonite for the seat of North Rockhampton. Former Premier William Kidston had left the Labour Party and formed his own party with support from moderates including fellow Rockhampton man Brennan. The election left Kidston as a minority premier but within a year he merged with Robert Philp’s conservatives, Philp briefly replacing him as premier. Brennan joined their new Liberal Party which held government under Kidston and later Digby Denham. Brennan resigned in 1912 when the seat of Rockhampton North was abolished. On retirement he moved to Wooloowin. He was buried here in 1917 next to his son William who died at Gallipoli.

Charles Moffatt Jenkinson (1865–1954) was a political contemporary of Brennan. Born in Birmingham, England in 1865, Jenkinson emigrated to Australia in 1883 and worked as a sports journalist before becoming proprietor at the South Brisbane Herald. In 1902 he was elected to Wide Bay as an opposition MP and year later moved to the seat of Fassifern. Though dismissed as a “sanctimonious job hunter” by the Brisbane Worker, he refused ministerial office. The highlight of his parliamentary career was an eight-hour filibuster, though he later voted for time limits to deny this expedient to others. In 1912 he became a Brisbane city alderman and was elected mayor in 1914. He immediately set out his vision for a new city hall at Albert Square (now King George Sq) and the foundation stone was laid in 1917. Jenkinson retired from council in 1916 and helped establish the large wartime Queensland Patriotic Fund for army wives and children. He returned to the Herald and in 1922 was described as “one of the regulars at Ascot and Albion Park racecourses”. He died aged 94 in 1954.

One of Lutwyche’s better known graves belongs to musician Harold “Buddy” Williams. Country and western music emerged out of the Appalachian mountains in the 1920s and singers like Jimmie Rodgers became popular with the rise of radio. Born in Sydney in 1918, the young Williams heard Rodgers’ music at a Dorrigo dairy farm and started busking illegally on the NSW North Coast as “the Clarence River Yodeller”. He enlisted in the Second World War and was seriously wounded at the battle of Balikpapan in Borneo. After the war Williams toured with the rodeo circuit and took his own variety show across Australia. He achieved lasting fame when fan Bert Newton had him on his TV show in the 1970s. Williams died of cancer in 1986. He was regarded as Australia’s first country star influencing those who followed including Slim Dusty. Williams was buried next to his daughter Donita who was killed in a traffic accident in Scottsdale, Tasmania in 1948, aged just 21 months. His grave contains a drawing of a guitar and words from his song Beyond the Setting Sun.

Buried in the Catholic portion is Patrick Short, Queensland’s first native-born police commissioner. His Irish parents Patrick and Mary Keogh emigrated to Ipswich in 1855. Patrick senior ran an engineering and blacksmith’s works though he died in 1862 when his son was three. Starting in the building trade, Patrick junior worked in south-west Queensland before joining the police force in 1878 and was posted to St George. He married Irish Catholic Eleanor Butler in 1880 at Roma. There were rumours that year that members of the Kelly gang had escaped Victoria so Short was assigned to border patrol. Though talk persists to modern times that Steve Hart and Dan Kelly lived out their lives in southern Queensland, Short found no trace of them and went back to regular duties. In almost half a century of service, he rose through the ranks becoming chief inspector in 1916 and commissioner five years later. He retired to Clayfield in 1925. A horse lover, Scott helped develop the police stud at Springsure and like Jenkinson, was often found at Brisbane racecourses. He died in 1941, aged 81.

Though the war had ended, there was tragedy on February 19, 1946 when an RAAF Lincoln bomber crashed at Amberley Airport near Ipswich killing 16 airmen. The plane was flying RAAF men home from Laverton near Melbourne but overshot the landing strip. Witnesses said the pilot retracted the under-carriage and attempted to lift the plane for a second circuit but it failed to respond and crashed before bursting into flames. The sixteen are buried together at Lutwyche. “Individual identification was not possible”, according to the grave plaque.

Lieutenant George Witton was a Boer War veteran, and a co-accused of Harry “Breaker” Morant. Witton was born to a Warrnambool, Victoria farming family in 1874. When the Second Boer War broke out in 1899, patriotic Australian colonies including Victoria rushed to send troops to fight in the conflict on the side of the British Empire. Witton served as a gunner before the war before enlisting in the Victorian Imperial Bushmen. In South Africa in 1901 he was recruited for the Bushveldt Carbineers, an irregular mounted infantry regiment, reporting to fellow lieutenant Morant. After the Boers murdered a captured British officer, Morant and another lieutenant Peter Handcock found Boer soldier Floris Visser with the murdered officer’s papers. Though Witton objected, they killed Visser after a de facto court-martial. That was one of six “disgraceful incidents” including the shooting of six surrendered Afrikaners cited in a letter signed by 15 Carbineers, which led to charges of several officers. Morant, Handcock and Witton were all charged with Visser’s killing. Morant infamously testified they shot him under “rule 303” referring to the 0.303 inch cartridge used in British Army rifles. Morant and Handcock were sentenced to death for murder. Witton was convicted of manslaughter and released in 1904 after Australian government intervention. In later life he was a succesful pastoralist and director of a Biggenden cheese factory. He died of a heart attack, aged 68, in 1942. He published his version of events in Scapegoats of the Empire: the true story of Breaker Morant’s Bushveldt Carbineers in 1904, though the book was hard to get, with many believing it was deliberately suppressed. In 2010, the British Government rejected a petition to review of the convictions of Morant, Handcock and Witton.

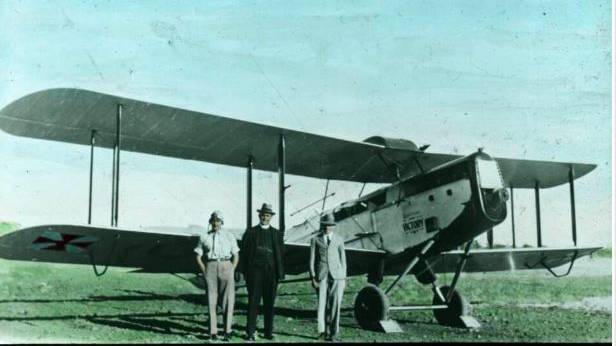

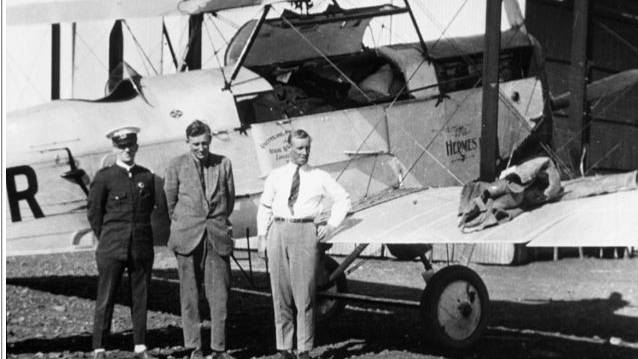

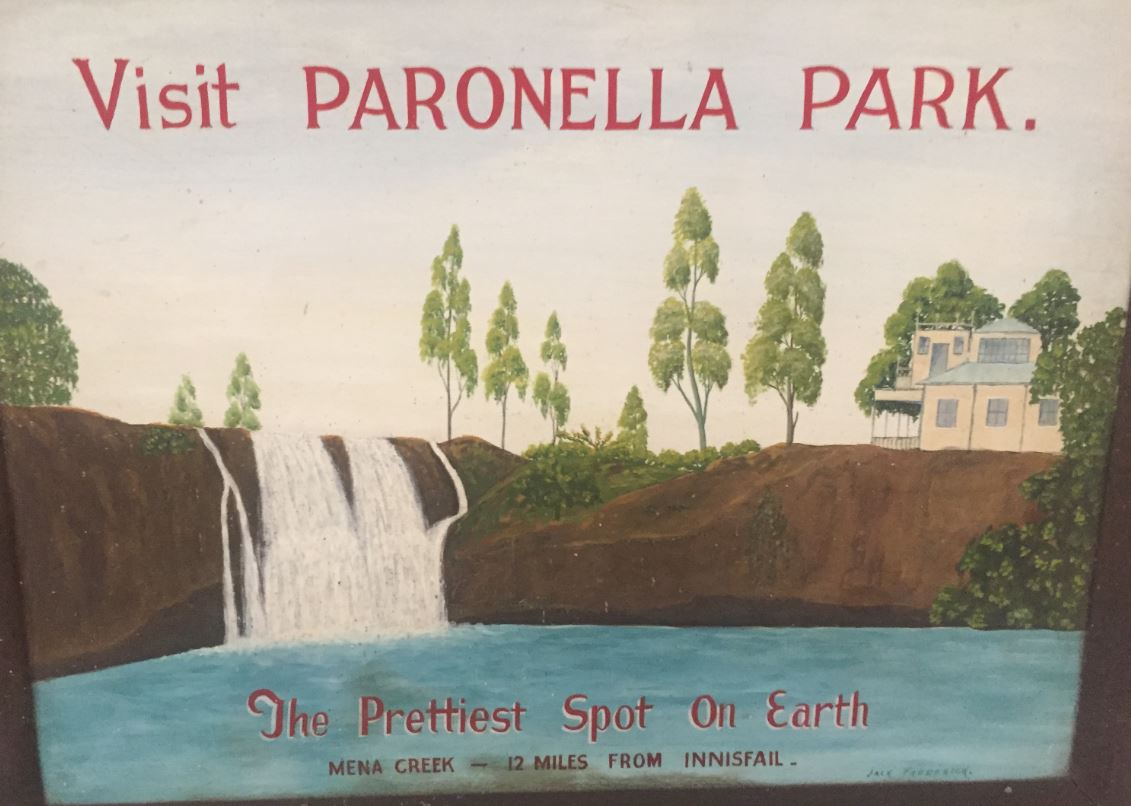

I’d driven the road from Townsville to Cairns in 2013 but at that time I’d not heard of Paronella Park. I headed up that way again in 2017 and in the intervening years I’d heard multiple times Paronella Park was worth a visit and had won many tourism awards. So I added it to my itinerary between Cardwell and Innisfail. The park is not new, it has been open since 1935. As I drove north I saw many billboards advertising its charms and wondered why I didn’t notice it before. Was it simply clever marketing in the last few years that had raised its profile?

I’d driven the road from Townsville to Cairns in 2013 but at that time I’d not heard of Paronella Park. I headed up that way again in 2017 and in the intervening years I’d heard multiple times Paronella Park was worth a visit and had won many tourism awards. So I added it to my itinerary between Cardwell and Innisfail. The park is not new, it has been open since 1935. As I drove north I saw many billboards advertising its charms and wondered why I didn’t notice it before. Was it simply clever marketing in the last few years that had raised its profile?

José first saw his park in 1914 but it wasn’t until 1929 he was in a position to buy it which he did for £120. Immediately he got to work building his pleasure gardens and reception centre for public enjoyment. Paronella was strongly influenced by the Moorish architecture and gardens of Spain, and the design of villa gardens visited during his European honeymoon. He also admired the work of Antonio Gaudi, and created garden elements inspired by the Alcazar Garden in Seville and the Botanic Gardens in Madrid.

José first saw his park in 1914 but it wasn’t until 1929 he was in a position to buy it which he did for £120. Immediately he got to work building his pleasure gardens and reception centre for public enjoyment. Paronella was strongly influenced by the Moorish architecture and gardens of Spain, and the design of villa gardens visited during his European honeymoon. He also admired the work of Antonio Gaudi, and created garden elements inspired by the Alcazar Garden in Seville and the Botanic Gardens in Madrid.

North West Queensland is full of the most amazing wildernesses but December is not the best time to go exploring. The intense heat and constant attention of flies make any outdoor adventure difficult. Nonetheless I was keen today to check out a place called Mt Frosty. Its name alone might cool me down.

North West Queensland is full of the most amazing wildernesses but December is not the best time to go exploring. The intense heat and constant attention of flies make any outdoor adventure difficult. Nonetheless I was keen today to check out a place called Mt Frosty. Its name alone might cool me down.

After 3km the dirt road petered out at this water outstation for cattle. There was no defined track any further and I thought this was a wasted trip. But when I stopped and got out of the car, I almost immediately saw two things that assured me I had arrived.

After 3km the dirt road petered out at this water outstation for cattle. There was no defined track any further and I thought this was a wasted trip. But when I stopped and got out of the car, I almost immediately saw two things that assured me I had arrived. Off to my left were the rusting iron remains of mineworks while straight ahead and deep down below there was the impressive two-sided tailings waterhole, complete with its own rusting campervan. The whole scene in this remote landscape reminded me of Mad Max.

Off to my left were the rusting iron remains of mineworks while straight ahead and deep down below there was the impressive two-sided tailings waterhole, complete with its own rusting campervan. The whole scene in this remote landscape reminded me of Mad Max. When I walked around the back of the waterhole more of the mine structure came into view. Mt Frosty gets its name from the quartz that litters the ground. But what did they mine there? When I went back to my computer later that day, I found the information on Mt Frosty mine was contradictory. Someone said it was a gypsum mine, another called it calcite, but the best documented evidence I found was that it was a limestone mine.

When I walked around the back of the waterhole more of the mine structure came into view. Mt Frosty gets its name from the quartz that litters the ground. But what did they mine there? When I went back to my computer later that day, I found the information on Mt Frosty mine was contradictory. Someone said it was a gypsum mine, another called it calcite, but the best documented evidence I found was that it was a limestone mine. The mine was owned by local legend Clem Walton (who also founded nearby

The mine was owned by local legend Clem Walton (who also founded nearby  The Mad Max feeling grew with all the graffiti on the mine works scattered up the hill.

The Mad Max feeling grew with all the graffiti on the mine works scattered up the hill. This photo reminded me of a ski resort. More particularly it reminded me of the

This photo reminded me of a ski resort. More particularly it reminded me of the  In his autobiography Aussie Rogue Raymond D. Clements described a time when he and a mate quit work at Mount Isa Mines after just four hours. His friend got a job on a cattle station near Dajarra while Clements got a job at Mt Frosty working for Walton. Clements reckoned his friend had the better deal, “you won’t die of led (sic) poisoning”.

In his autobiography Aussie Rogue Raymond D. Clements described a time when he and a mate quit work at Mount Isa Mines after just four hours. His friend got a job on a cattle station near Dajarra while Clements got a job at Mt Frosty working for Walton. Clements reckoned his friend had the better deal, “you won’t die of led (sic) poisoning”. Walton sent newcomers like Clements out to crush rocks with 15-pound sledgehammers to test their mettle. Clements passed muster and graduated to work a drill for blast holes and helped the foreman charge up and fire the rockface. This photo above reminds me of the German defences on Normandy, a turret bristling with guns.

Walton sent newcomers like Clements out to crush rocks with 15-pound sledgehammers to test their mettle. Clements passed muster and graduated to work a drill for blast holes and helped the foreman charge up and fire the rockface. This photo above reminds me of the German defences on Normandy, a turret bristling with guns. Clements said that after the tip truck dumped its load of limestone on the large cast iron screen, workers broke it up with sledgehammers. The broken rock went through the crushing plants and was stockpiled until roadtrains took it to the Mount Isa copper smelter. This photo above reminded me of another nearby abandoned mine at

Clements said that after the tip truck dumped its load of limestone on the large cast iron screen, workers broke it up with sledgehammers. The broken rock went through the crushing plants and was stockpiled until roadtrains took it to the Mount Isa copper smelter. This photo above reminded me of another nearby abandoned mine at  Clements said the crushed limestone was used for flux in the smelting process of copper. Smelting no longer uses limestone and the mine was abandoned in the 1960s. However there is still plenty of valuable minerals around here. Australian mining company Hammer Metals has formed a joint venture with Swiss-giant Glencore (current owners of Mount Isa Mines) after acquiring

Clements said the crushed limestone was used for flux in the smelting process of copper. Smelting no longer uses limestone and the mine was abandoned in the 1960s. However there is still plenty of valuable minerals around here. Australian mining company Hammer Metals has formed a joint venture with Swiss-giant Glencore (current owners of Mount Isa Mines) after acquiring  Having checked out the buildings, it was time for a closer investigation of the waterhole and its tunnels where the mining operations took place. Not to mention the campervan. How did it end up there?

Having checked out the buildings, it was time for a closer investigation of the waterhole and its tunnels where the mining operations took place. Not to mention the campervan. How did it end up there? The van was in a dilapidated state wedged tight between rocks. I wondered if it had been thrown over the top, but it wouldn’t explain its careful position and its relatively undamaged bodywork.

The van was in a dilapidated state wedged tight between rocks. I wondered if it had been thrown over the top, but it wouldn’t explain its careful position and its relatively undamaged bodywork. But to drive it down such rough terrain also looked unlikely, unless it was driven completely on its rims. One thing I am certain of is there would have been one last almighty party to farewell it, overlooking the amazing lake with its impressive overhangs.

But to drive it down such rough terrain also looked unlikely, unless it was driven completely on its rims. One thing I am certain of is there would have been one last almighty party to farewell it, overlooking the amazing lake with its impressive overhangs. References to Mt Frosty are few and far between. In 1975 Nationals state member for Mount Isa Angelo Bertoni spoke in parliament about the joys of his electorate in a debate about tourism. Mount Isa, he said, was a jumping-off point for other attractions. “It is rich in native flora and fauna, and Aboriginal paintings. One Aboriginal fertility painting in rock 30 miles from Mount Isa has been there for 2000 years. Tours can be taken to the Aboriginal paintings, and from there to what we call Mt. Frosty, with its lime deposits and pools of water. One could fossick around there for hours and hours. The tourist to the Inland will feel that here is something quite different from what can be seen along the coast.”

References to Mt Frosty are few and far between. In 1975 Nationals state member for Mount Isa Angelo Bertoni spoke in parliament about the joys of his electorate in a debate about tourism. Mount Isa, he said, was a jumping-off point for other attractions. “It is rich in native flora and fauna, and Aboriginal paintings. One Aboriginal fertility painting in rock 30 miles from Mount Isa has been there for 2000 years. Tours can be taken to the Aboriginal paintings, and from there to what we call Mt. Frosty, with its lime deposits and pools of water. One could fossick around there for hours and hours. The tourist to the Inland will feel that here is something quite different from what can be seen along the coast.”