In the 1863 song Pat Murphy of Meagher’s Brigade, “honest Pat Murphy” sings ballads at the Irish Brigade campfire the night before battle. The following day, “a hole through his head from rifleman’s shot” ended Murphy’s life. The Brigade lamented that “no more in the camp will his laughter be heard, or his voice singing ditties so gaily”. The fictional Pat’s tragic story was depicted through Murphy’s own medium. His imagined tale captured the spirit of front-line singing culture and reflected the experience of all Irish in the war.

Over 200,000 Irish-born soldiers fought in the American civil war as did thousands more second generation. Their exploits were celebrated in Pat Murphy and 150 other songs written between 1861 and 1865. These ballads are the subject of Catherine Bateson’s 2018 doctoral thesis The Culture and Sentiments of Irish American Civil War Songs which explores what they said about Irish loyalty and devotion to the Union. Bateson found that support for the Irish nationalist cause in 1860s America was complicated, at best. Mainly she found a pervading American identity, “that the Irish fighting and living through the war were stressing to society through song that they were committed to the United States as Americans first and foremost.”

Irish music and songs were popular in America before the civil war, widely circulated by oral tradition, songsheets and broadsides. Tunes carried their own meanings and ballads dedicated to the Irish Brigade used American airs which strengthened the lyrical message of loyalty to America. Dubliner Thomas Moore’s influential 1808 songbook Irish Melodies spread rapidly through America, many songs taking on American identities. Also popular was Thomas Davis‘s Spirit of the Nation (1843). Fellow Young Irelander Thomas Francis Meagher noted the songs sung at bivouac before the 1861 Battle of Bull Run were “mostly those that Davis wrote for us.” Another Irish song The Irish Jaunting Car had a marching-pace tune which became popular especially when Confederates adapted new words to it in The Bonny Blue Flag. Northern soldiers produced their version A Reply to the Bonnie Blue Flag using the same Irish air.

The air inspired Irish Volunteer No. 3 (1862) about General Michael Corcoran. This song about Irish wartime service focusing on American loyalty, set to an old Irish tune that became part of an American musical tradition, showed how blurred Irish American identity was becoming. The tune was used in another important Irish wartime song What Irish Boys Can Do which answered anti-Irish nativist criticisms showing the diaspora’s devotion to the Union cause. The American Fenian ballad What Irishmen Have Done was also based on The Irish Jaunting Car. The most famous civil war song When Johnny Comes Marching Home was not Irish, but Patrick Gilmore, the Galway-born Union Army bandmaster and conductor, took a traditional Irish tune Johnny, I Hardly Knew Ye and used it as the foundation of his When Johnny Comes Marching Home lyrics in 1863.

Music and songs were a crucial part of a soldier’s experience during the American Civil War and musical melodies and ballad songs permeated every camp. Corporal John Dougherty of the 63rd New York Regiment told his mother of the general singing atmosphere. “The cheerful spirit of the Irish Brigade made the road seem short, the funny joke and merry laugh of the men at all times whether on the battlefield, on the march or in camp makes the Brigade the envy of the rest of the army – they would go along in silence looking sad while the Irish men would be laughing and singing.” William McCarter of 116th Pennsylvania journeyed to war “accompanied by the voices of the regiment” while military bands mixed the Irish and American airs of Johnny is Gone for a Soldier, The Star Spangled Banner and John Brown’s Body. While a prisoner of war, Michael Corcoran put on concerts with his men for Confederate captors who were “highly delighted with the performance, until, in grand strains, we gave them Hail Columbia.” Mostly, they didn’t mind the musical teasing.

Musicians brought their instruments to the field. Irish Brigade chronicler David Power Conyngham remembered Christmas night 1862. “Seated near the fire was Johnny Flaherty, discoursing sweet music from his violin. Johnny hailed from Boston; was a musical genius, in his way, and though only fourteen years of age, could play on the bagpipes, piano, and Heaven knows how many other instruments; beside him sat his father, fingering the chanters of a bagpipe in elegant style.” Letters home revealed a musical knowledge with one writer wanting to see “Jeff Davis on a sour apple tree” quoting the popular Union air John Brown’s Body while McCarter referenced another song writing of three rousing cheers for Philadelphia and “the girls we left behind us.”

County-Meath born Charles Graham Halpine was the most prolific Irish wartime lyricist and poet in America, known for fictional comic creation Private Miles O’Reilly which appeared in the New York Herald from 1863. His work was collated into The Life and Adventures of Private Miles O’Reilly in 1864. The Irish American newspaper printed ballad verses such as Camp Song of the Sixty-Ninth and War Song of the Irish Brigade, the latter sung to the tune of the Star Bangled Banner.

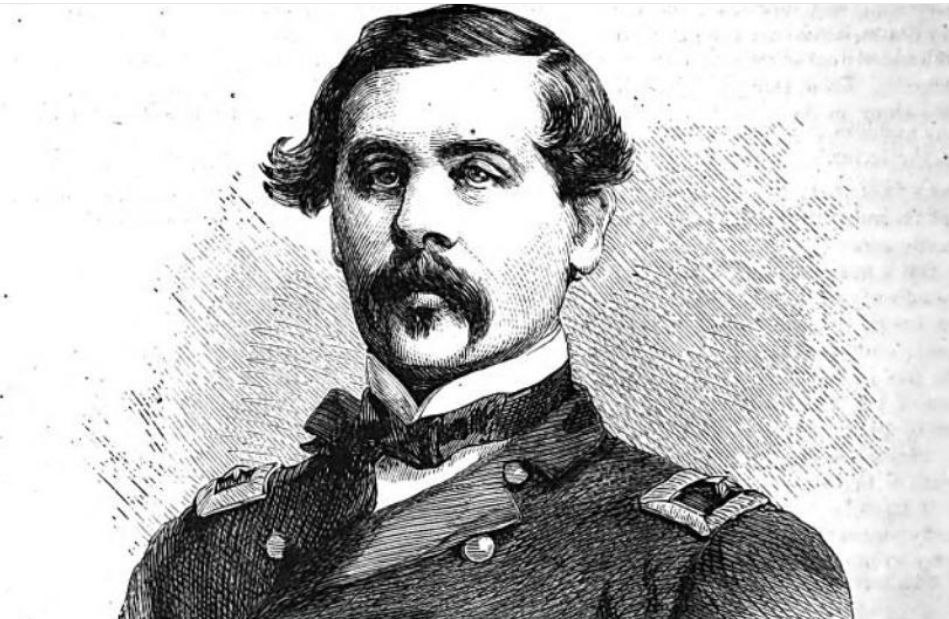

The gallant bravery of the 69th Regiment and the Irish Brigade was a common theme in songs from First Bull Run onwards and lyrics were dedicated to two Irish-born leaders. Thomas Francis Meagher and Michael Corcoran embodied the Irish American Civil War experience and were both extolled in verse. The Escape of Meagher, written in 1852 and disseminated as a broadside in both Ireland and America, sang of Meagher’s escape from exile on Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). When he arrived in New York City, Meagher was greeted by diasporic enthusiasm: “it’s plain to see, for Erin go Bragh, the sons they still have a grah”.

Corcoran was even more lauded than Meagher. The song To the Glorious 69th! described the 69th’s chivalry at Bull Run under “brave Commander” Corcoran. “They stood in the hot battle, where balls like hailstones flew, Until the rebel ambush-host with balls did pierce them through.” Another song noted how Corcoran with sword in hand commanded “these sporting boys from Paddies’ land” and as the battle raged they “stood the plain for many an hour, though shot and shell like rain did shower, To prove their valour, tact and power as gallant sons of Erin.” The song Battle of Bull Run was a detailed account of how the Union lost the battle to superior Confederate firepower despite Irish bravery, “we did retreat but were not beat” and ends with Corcoran telling his men “we’ll make them pay some other day”.

Bull Run was the foundation for subsequent productions of Irish wartime history told through song. Long Live the Sixty-Ninth hailed them as they came home to New York “black with battle-smoke, radiant with fame”. The 69th was the founding regiment of the Irish Brigade, commanded by Meagher and many song sheets were penned in its honour. The War Song of the Irish Brigade of November 1861, included reference to the Wild Geese’s flight and how Irish Americans would remember famous battles fought by previous Irish Brigades: “Fontenoy! Fontenoy! We ring out with great joy, And ‘remember Limerick’, will come from each boy.” The first of numerous ballads called The Irish Brigade (1862) claimed no Irish soldier was afraid of battle. “There ne’er was traitor or coward, In the ranks of the Irish Brigade.” Irish Brigade songs sang of the mid 1862 Battle of Fair Oaks and the Seven Days Battles. America’s Irish Brigade! had a verse saying “In the seven days’ fight, sure I stood at my post, And each pop of my gun made some Rebel a ghost.”

Other songs focused on darker times. The Irish Brigade in America was about the fatal charge at Fredericksburg’s Marye Heights on December 13, 1862, where nearly half the Brigade was lost. “With bayonets fixed they charged the heights, and death soon scattered round. And thousands of the Southerners lay dead upon the ground.” The Union did not gain the victory the ballad implied and defeat was compounded in Irish eyes by the Emancipation Declaration which came into effect in 1863. As a Halpine songs went “To the flag we are pledged – all its foes we abhor; And we ain’t for the nigger, but are for the war!” The Irish community was blamed for the subsequent New York draft riots of 1863 though Irish war songs ignored this topic. Their focus remained on loyalty to America, and suggests most Irish Americans detested the unfairness of the draft rather than abolitionism itself.

While Irish support for the war dropped after Fredericksburg, Bateson says that lyricists penned verses that continued to extol Irish service and pride in the war effort. Hugh F. McDermott’s January 1863 ballad ode The Irish Brigade drew inspiration from Marye’s Heights and Meagher’s inspiring leadership before the fight. “With shout and yell, and stunning peal, Their vengeance leapt upon their steel.” Its refrain was that sacrifice with honour and noble battlefield endeavours should be remembered and commemorated. It was hugely popular even outside the Irish communities in New York and Boston.

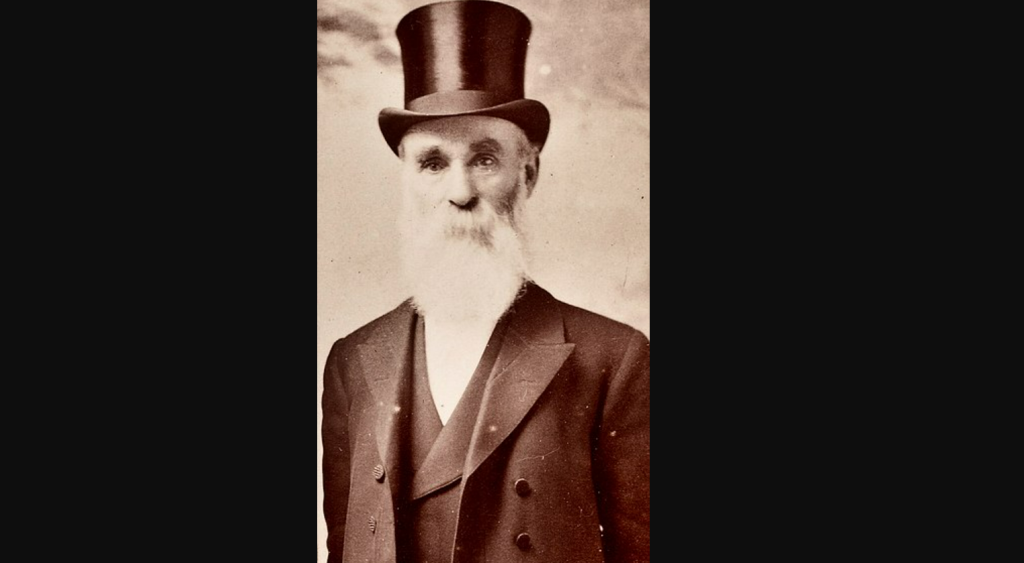

Though stuck in Confederate prisons for the early part of the war, Michael Corcoran remained the most frequent figure lauded in Irish wartime ballads. Corcoran had served with the militia since 1849 when he moved to the United States, and steadily rose through the ranks before becoming colonel. The first ballad in his honour predates the war. Corcoran refused to participate in a parade for Prince Edward of Wales who visited America in October 1860. Corcoran was imprisoned and awaiting a court martial trial when southern states seceded from the Union. Corcoran was released after pledging loyalty to the Union and offering his militia to defend Washington. The 69th New York State Militia mustered into service in May 1861. Col. Corcoran and the Prince of Wales retold Corcoran’s version of events. “Through the street and the parks the Militia did start, For to take a part in the Royal parade: There was one stood alone…. [Corcoran] would not comply for to honor the King. Court-martial was ordered the jury was panelled, To try this brave Hero for no other offence.” The song detailed the 69th’s journey to their compound at Arlington Heights, renamed Fort Corcoran.

At Bull Run, Corcoran was taken prisoner of war. Battle of Bull Run depicted him as a brave commander rallying Irish soldiers. At the end, the “gallant Colonel Corcoran”’ was on the ground, “weary and fatigued and exhausted from his wound… Cried unto his gallant men brave boys I’m not undone.” Several songs made reference to his subsequent year-long imprisonment, even non-Irish songs, such as We Will Have the Union Still which expressed how the whole Union Army would avenge the insult of Corcoran’s battlefield capture. After his release in August 1862 the ballad Corcoran! The Prisoner of War said he had “tendered his sword and his life” to America, implying that other Irish should follow suit. The freed Corcoran would “capture ould Jefferson Davis; And will wallop the rebels like blazes” as another ballad put it.

Corcoran’s lauding confused matters while he was in prison and the 69th Regiment was rolled into the Irish Brigade, under Meagher. Corcoran supporters were frustrated the Brigade did not wait for his release, especially as rumours surfaced of Meagher’s supposed drunkenness at Bull Run. Despite Meagher’s erratic behaviour, the songs about him were positive. “That gallant MEAGHER fleets swiftly past; Through teeming groans, and clash and jar, His trumpet voice thus sounds afar: ‘Again to the charge, old Erin’s sons!” War Song of the Irish Brigade is also glowing. “Our leader is youthful, and manly and brave, The pride of our race: and a lover of glory… Then Meagher lead the way. We’re eager for the fray, With thy spirit to cheer us we’ll soon win the day.” Halpine’s Miles O’Reilly, heaped praise on Meagher’s leadership in a fictional meeting with President Lincoln in 1863. O’Reilly informed Lincoln that because “the poor boys of the Irish Brigade’ had experienced ‘days of its hardest fights under General Meagher”, their leader “ought to have two stars on each shoulder, or there could be no such thing as justice to Ireland”. What Irish Boys Can Do (1863) used Meagher to push back against Know Nothingism, reminding Americans that in the present war “Let no dirty slur on Irish ever escape your mouth”.

Yet even a year into Meagher’s tenure, songs about the Brigade continue to refer to “Bould Corcoran leading us”. Meagher would not have been too upset and accuracy came a distant second to telling a good story. For those listening to ballads about Irish American Civil War service, it was the battlefield stories and war sentiments that mattered, not nuanced details about accurate units and command. The song Return of Gen. Corcoran of the Glorious 69th (1862) sang about how Meagher drew on the spirit of the original Irish Brigade to spur on the 69th New York at Bull Run and Fair Oaks: “As at the charge of ‘Fontenoy’, our brave men of to-day, With gallant Meagher, drove the foe, in terror and dismay – For at the battle of ‘Fair Oaks, as at the ‘Seven Pines’, The Irish charge, with one wild yell, broke through the rebel lines.”

After his release Corcoran established his own command and recruited some of his old 69th New Yorkers, for his “new brigade of Irishmen who would preserve America”. Corcoran’s Legion mostly remained in New York and experienced little action compared to the Brigade’s bloody involvement on major battlefields. That did not stop songs in the Legion and Corcoran’s honour though one 1863 ballad complained about lack of action. “So here we’re doomed to swear and sweat, On Bull Run’s bloody borders.”

It was not a good year for the Irish leaders. Meagher resigned in May 1863 protesting against the slaughter of his Brigade at Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Corcoran died ingloriously in December, falling off his horse after a drinking session with Meagher. Corcoran was mourned in song, but the number of ballads dropped off. The Irish Brigade, minus Meagher, was much diminished, which was recognised in song “Our Brigade exists no longer – they have gone – the good the true; Pulseless now, the gallant hearts that a craven feat ne’er knew.”

Older antipathies emerged with the prospect of battle-hardened Irish troops going home to fight for independence from Britain. The 1862 song The Irish Volunteers looked forward to this under Meagher’s leadership: “Long life to Colonel Meagher, he is a man of birth and fame And while our Union does exists applauded be his name.” This was what Fenians wanted, though Meagher was a lukewarm member at best. Pat Murphy of Meagher’s Brigade also sang he would rather fight the British than the Confederates. “Now, if it was only John Bull to the fore, I’d rush into battle quite gaily; For the spalpeen I’d rap with a heart an’ a half, With my elegant Sprig of Shillaly.” The reality was different as Lamentation on the American War showed after 1864’s bloody battles. “Heaps of Irish heroes brave on the plains there lay, That was both killed and wounded there all in America.” Instead of fighting the Saxon, most of the Irish Brigade were dead as another song lamented: “Themselves, with the mournful past, have fled… Many a tear and tender thought will be given the lonely graves.”

The post war “Fenians Ever More” gave the lyrical impression that America would come to Ireland’s aid: “with Yankee ships and Irish hearts”, Irish and American soldiers would “cross the mighty Main”. Instead the United States discouraged the Fenian invasions of Canada while the Irish uprising of 1867 was a miserable failure. Meagher, too, was wary of Irish rebel activity after the war. When he became acting governor of Montana, which bordered Canada, he told Secretary of State William Seward that he had met local Fenians and though he was sympathetic, he said that “as an officer of the United States, I felt bound in honour, as well as by a conscientious regard to my official obligations, not to say or do anything which might be at variance with the policy and duty of the Government.” Like the wartime ballads about him, Meagher put his loyalty to America first. So did countless other Irish Americans. America, with its dreams of liberty and democracy, was everything they wanted Ireland to be. As one song put it “now Erin’s Green flag is blended Among with the Red, White and Blue.” The Irish especially needed to show that loyalty to other Americans: “To the Banner of Freedom, to the red, white and blue, The brave Irish soldier must ever prove.” The Irish took up arms as American citizens and defended its unity. America had become their home nation, and the Irish were citizens twice over, as Halpine wrote, “by adoption and by service”.

Meagher’s death in 1867 and the deaths of other prominent figures including Corcoran, Halpine and Archbishop John Hughes was a huge blow to Irish American identity after the war. Yet its ethos lived on in ballads. The 1868 song America to Ireland suggested survivors carried on the legacy of Irish American Civil War heroes: “The leaves of the Shamrock are spreading a-far, And we honor the heroes who bare them, Where Sheridan, Corcoran, Mulligan, Meagher, Like pillars of fire went before them.”